Breast Health In The Time Of COVID-19: Volume 5

Schedule Your Mammogram

It seems only fitting to come full circle in this final volume to talk further about mammograms. Mammography is the workhorse in our efforts to identify and treat breast cancer at its earliest stages.

I spoke in the first volume about the difference between screening and diagnostic mammograms, and you may want to refresh your memory on this here. I am focusing on screening mammograms in this installment. I will again emphasize that if you have any breast symptom, it should be evaluated promptly, and any imaging would be diagnostic, and NOT a screening.

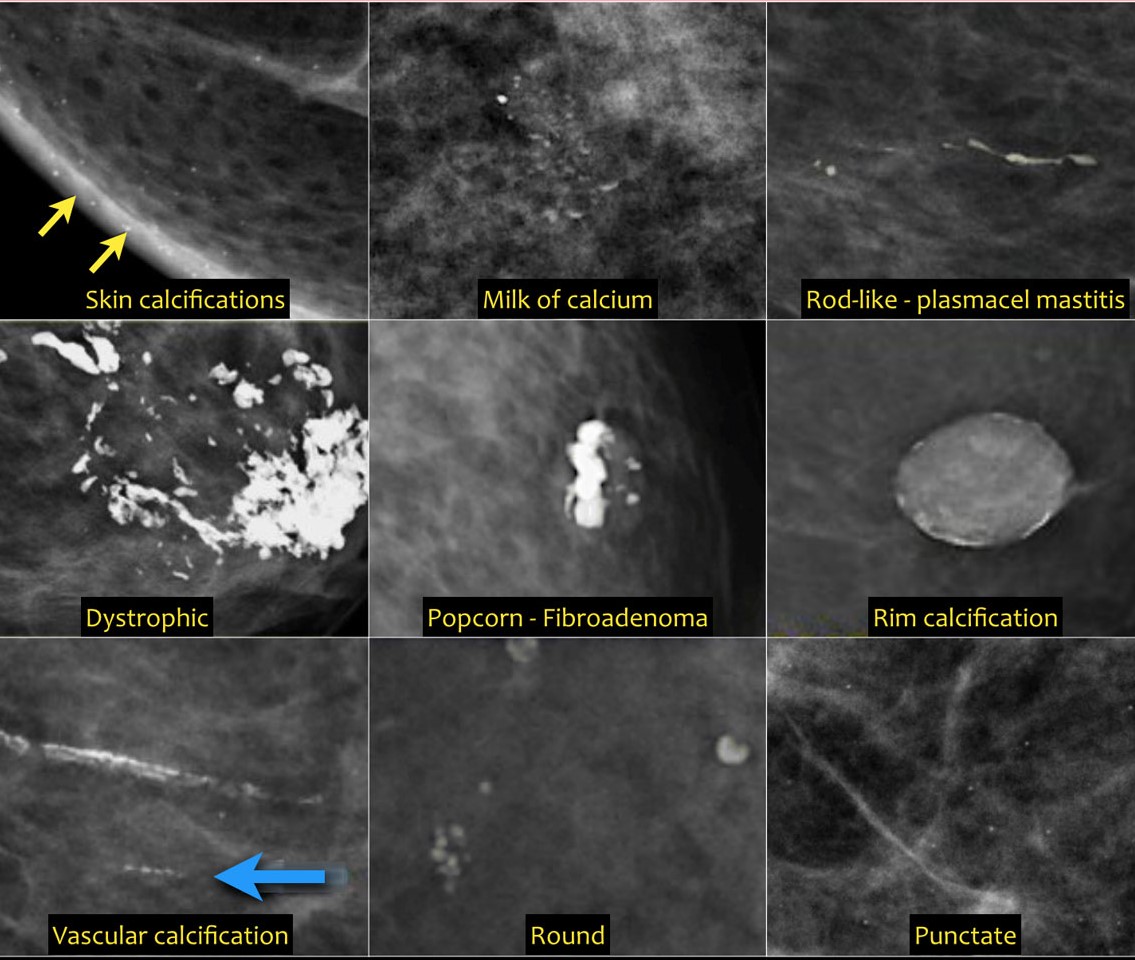

Benign calcifications

Decades of experience around the world with X-rays of the breast has led to consensus on what findings on screening mammography are suspicious enough to warrant a biopsy. The most common suspect findings consist of abnormal calcifications, or various density differences in the breast.

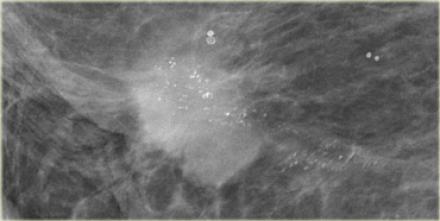

Highly suspicious calcifications

There are multiple types of calcifications that can be seen. Some are known to be virtually always benign, some are almost proof positive of cancer, and some are suspicious for cancer but can also represent benign disease. The most common type of calcifications that lead to a biopsy are called microcalcifications.

Highly suspicious density

Similarly, the list of density variations is quite long, and some require additional evaluation. Breast ultrasound plays a major supporting role for evaluating atypical breast densities, since the findings on ultrasound can help in targeting for biopsy by core needle. Ultrasound plays little role in evaluating calcifications, since these are almost never seen on ultrasound.

There are currently two different options for mammogram screening. The basic digital screening includes two views of each breast, one set taken vertically, and the other view done obliquely along the “long axis” of the breast. These two views are called “CC” and “MLO”. The amount of radiation required for this set of films is only about 15% of the radiation any person receives in an entire year from just natural environmental sources, such as sunlight, and from radioactive earth minerals (called background radiation).

The second option for screening is usually referred to as “3D mammography”. These films require about 1-2x as much radiation, but this is still a very low dose, and they provide a more detailed view of the breasts. The two basic views are supplemented by rotating the Xray beam in an arc over the breast, and the images are digitally formatted into a series of many thin sliced views of the breast. This means that instead of four pictures of your breast for the radiologist to review, there are approximately between 300-500!

For many women, this extra detail may be more than really necessary, but it can be especially helpful in women with “dense breasts”, and with women who have a lot of background tissue distortion in their breasts, for example after prior breast surgery. Breast tissue typically becomes less glandular after menopause, and for most women in their late 60’s and older, the basic views are likely sufficient. You can discuss with your doctor which option seems most appropriate for you, and how often you should be screened.

It is advisable to go to the same center each year for your screenings since a comparison of current films with prior studies is an essential component. If you do need to change locations, be sure to obtain a disc of your previous mammograms to take to the new facility.

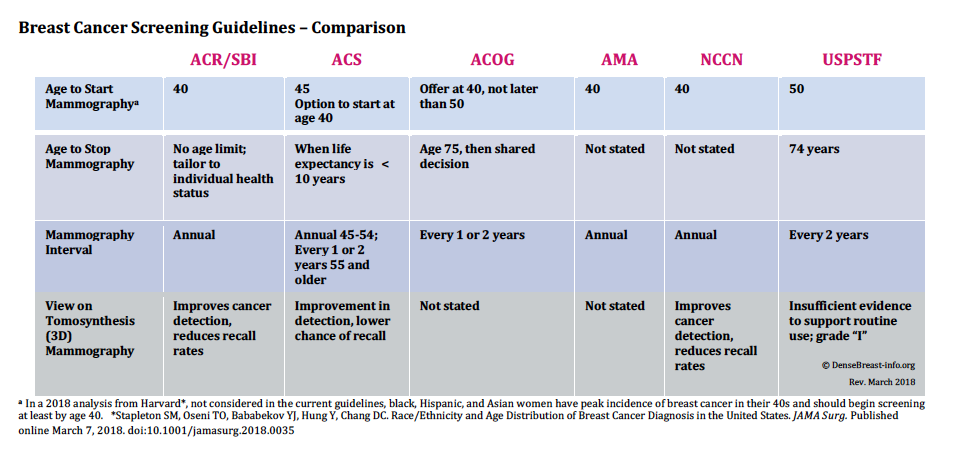

There are different opinions on when screening should begin, how often, and for how long. Some authorities, such as the American College of Radiology, and the American Society of Breast Surgeons, recommend beginning at age 40, continuing annually and indefinitely. The United States Public Safety Task Force (USPSTF) has the most lax recommendations, starting at age 50, and a two-year interval. Interestingly, the disruption of screening mammography during the current

Breast Care Roundtable in the COVID Age- April 20, 2020

pandemic will likely stimulate a re-evaluation of the guidelines. This concept was discussed in a webcast that I participated in just this week among thought leaders in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. What this means is that each woman would have an individualized screening schedule based on her risk factors, and perhaps also accounting for her own level of concern about breast cancer.

This concludes this series on Mammography and Breast Health. If you missed some or all of the earlier installments, here are the links:

Breast Health In The Time Of COVID-19: Volume 1

Breast Health In The Time Of COVID-19: Volume 2

Breast Health In The Time Of COVID-19: Volume 3

Breast Health In The Time Of COVID-19: Volume 4

I’d love some feedback. Feel free to comment, and stay safe!

I often post tips and information on my Twitter feed. You can follow me there @jskennedymd