Cancer in the colon or rectum often begins as a polyp, which is a non-cancerous growth in the lining of the large intestine. These growths develop because the cells have already had one or more of the mutations, but have not yet had a critical mutation that would transform them into cells with the ability to invade surrounding tissues. The cells that make up a colon polyp are already halfway there and our colon cancer prevention strategies are based on this understanding. We are able to look inside the colon with a lighted scope and remove these polyps, and thus prevent the possibility of progression to cancer.

Much has been learned about how cancer develops in the colon or rectum. The mucus cell lining of the intestines is continually renewing itself by continuous cell division, just like skin. It is important for the rate of cell division to be carefully controlled, such that there is just the right number of cells lining the intestine. The cell division is controlled by some of the genes that are located in the DNA of every cell. These genes, the “code” for the cells, are reproduced in each new cell. Usually, the information in the gene is reproduced exactly in each daughter cell, but every once in a while, there is a defect, or mutation, in the code as the new cells are made. Certain mutations may not make much difference, but there are some mutations that can alter the regulation of cell growth for all subsequent cell divisions.

We have learned to look for some very specific mutations in colon cells that are known to allow the cells to keep dividing continuously. It seems that a combination of mutations is what underlies the development of cancer so if just one mutation occurs in some cells somewhere in the colon, there may be no cancer. If in those mutated daughter cells there is another specific mutation or two, all the later daughter cells will have the potential to invade into surrounding tissues, and this is basically what constitutes cancer.

Incidence

Cancer arising in the colon or rectum is quite common in the US, being the fourth most common site for cancer.

One way of comparing how prevalent a cancer is is to compare how many cases are diagnosed for every 100,000 people in a given area. For the entire United States, the incidence of colon or rectal cancer is about 49 cases for every 100,000 people. Since the US population totals 307 million people, that comes out to over 150,000 new cases per year. This data comes from SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results), a division of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which combines colon and rectal cancers together.

In Georgia, the incidence rate is slightly lower, at 47/100,000, which means that about there are about 4,700 new cases per year. DeKalb County’s incidence rate is only 42/100,000, which translates into about 300 new cases per year. About 1/3 of these patients are treated at DeKalb Medical.

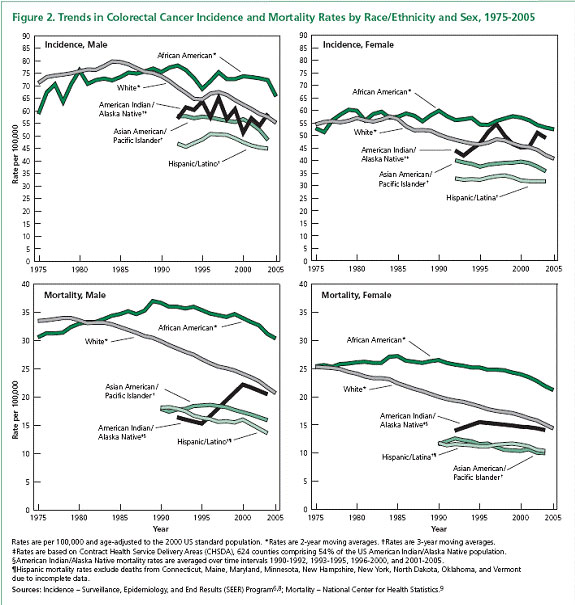

For reasons that are not clear, the incidence of colon and rectal cancer is higher in African Americans than in Caucasians, and particularly in men. The American Cancer Society shows this data in a table below that compares the data for men and women separately. It also shows the number of people who die from colon or rectal cancer each year in these subgroups, and it shows how the incidence and mortality rates have changed over the past 30 years. It is gratifying to see that both the incidence and the mortality rates are trending downward. But we still have a lot of room for improvement. It is hoped that if we can increase the number of people who get screened for colon and rectal cancer, that we can further decrease the number of people who die. As you can see, screening is probably most important for African American men, but it is, of course, important for everyone.

Symptoms

If cancer in the colon is causing symptoms, it has probably been present for some time since very small cancers usually don’t cause any problems. We want to find these cancers before they cause symptoms by looking for polyps and cancers in people who may have no evidence of cancer. We try to focus on those who, at least statistically, are likely to develop colon or rectal cancer. We recommend colonoscopy for patients once they turn 50 as these cancers are more common as you get older. For African Americans, screening is recommended to begin at age 45 or even earlier as the incidence is higher. If you have a family history of cancer, screening should begin earlier.

Even though screening is our primary recommendation for diagnosing colorectal cancer, there are going to be patients who have symptoms before a cancer is found. If you have any of these symptoms it does not necessarily mean you have colon cancer, but you should be checked.

There can be a change in your usual bowel habits. If you typically have bowel movements every morning, or twice a day, or every other day, and then you start having more or less frequent bowel movements, perhaps sometimes diarrhea and sometimes hard, or if you notice that the stools start coming out real thin like the width of pencil, or if you just become more constipated, these symptoms should be evaluated.

Rectal bleeding should always be taken seriously to determine the cause. Bleeding might be noted simply as some blood on the toilet paper when you wipe after a bowel movement. It might be noted as a pinkish tinge to the water in the toilet bowl after a bowel movement. You might notice blooding dripping from your rectum near the end of bowel movement, blood clots mixed in with the stool, or what looks like streaks of blood on the surface of the stools. Blood that has come from higher up in the intestinal tract may have a maroon color, or even black (this is called “melena”). In any of these cases, you should contact your doctor to determine the source of the blood. There are a number of different possible explanations including hemorrhoids, anal fissures, benign polyps, diverticulosis, ulcers, inflammatory disease of the intestines, malformations of the vessels in the bowel, or various types of cancer.

The other signs and symptoms listed are less specific to the possibility of colon cancer, such as abdominal pain, weakness, and fatigue, or unexplained weight loss. Such symptoms should still be discussed promptly with your doctor to determine the cause.

Diagnosis

There are various tests which may be used to identify problems in the colon, such as polyps, or cancer, or other abnormalities of the lining of the colon. Colonoscopy is often the test of choice since so much information can be gained from it.

A colonoscopy is often a part of the evaluation process. Your doctor will gather pertinent information from you to help decide what is the most likely explanation for your symptoms. Depending on your age, your specific symptoms, duration of symptoms, time since any previous colonoscopy, and any pertinent family history, among other things, your doctor may recommend a colonoscopy. This procedure involves the use of a long, thin, flexible tube with a bright light on the end, optical fibers, which transmit an image from the tip of the scope to a video output, and a channel for passing small biopsy devices to the tip. In most cases, the source of your symptoms can be identified. Any polyps (which could transform into cancer in the future if not removed) or cancers in the colon are almost always identified with this procedure.

Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy

In order to have a clear view of the inner lining of the colon, your doctor will give you a “bowel prep”, which is one of a variety of recipes which will wash out your colon over a day or so. You will need to take only clear liquids by mouth during the bowel prep. If there is any stool remaining in your colon, some of the colon linings may be obscured so it is important to make sure to follow the instructions for the bowel prep carefully.

There are a few different options for bowel preparation, varying in duration, potential side effects, and cost. Most physicians have a preference based on their own experience. The first priority is to use a prep that is safe for you, and all of the options usually are. If you have any chronic illnesses such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, or kidney disease then special consideration should be given to the ideal prep. Whichever is selected, the goal is to have a completely clean colon so that all of the linings can be clearly seen. If there is some stool remaining, it can obscure some of the colons, and polyps or other pathology might be hidden from view.

The procedure requires some sedation, almost always given by vein. You will not be able to drive immediately after the procedure so you will need to have someone with you to drive you home afterward. It usually only takes about 15 minutes. If any biopsies are needed, the results from the biopsy usually take a few days to get.

Screening

Since colon cancer in its early stages is usually without symptoms, we need to look for it and find it before it advances to a symptomatic stage. A number of different options exist to do this. We primarily rely on colonoscopy to screen for polyps and colon cancer currently, though there are some other options available.

As you are probably aware, there are a variety of screening tests recommended by physicians for the general population, such as mammography for women over age 40, skin exams to look for melanoma and other skin cancers, Pap smears for women, looking for female cancers, and colonoscopy for colon polyp and cancer screening. There are many factors taken into account when making a recommendation for a screening test. These factors include accuracy of a “positive” result, accuracy of a “normal” result, cost, availability, convenience, and risk, among others. A test may be extremely sensitive to detecting the condition being screened for, but if the test is too expensive, its use as a screening measure is limited. On the other hand, a test may be very simple and inexpensive, but it may not be accurate. There is no ideal screening test for colon cancer. Colonoscopy is considered the most sensitive and accurate test and has the advantage of allowing biopsies of suspicious areas. But it is relatively expensive, and inconvenient in comparison with the other options. Currently, in the US, this is still considered by most experts to be the best choice.

Barium Enema

Occasionally, colonoscopy cannot be completed safely, and in these cases, other methods might be considered. One method, called a barium enema, involves the instillation of barium through the rectum, so that it backfills the colon all the way around to the small intestine, while the abdomen is being viewed with real-time x-ray, called fluoroscopy. Although the colon is not directly visualized, the outline of the inner wall of the colon can be seen, allowing any medium to large polyps, cancers, and other abnormalities of the colon to be seen. This test is done much less often these days, but there are advantages in certain cases.

Rigid Sigmoidoscopy

There are other “scopes” that can be used to look at the inside of the colon. A 12″ inch hollow tube with a light and insufflation (pumping air in), called a rigid sigmoidoscope, gives a visualization of the last segment of colon, primarily the rectum. As you might imagine, it can be somewhat uncomfortable to insert this device into the rectum, and these days it is only occasionally used for screening for cancer. It does play an important role for surgeons in the context of planning surgery for cancer very close to the anus. This device is the best for determining accurately precisely how close to the anus cancer might be, information that is crucial for planning surgery for rectal cancer (one which is close to the anus).

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

There is also a shorter flexible scope, called a flexible sigmoidoscope, which allows visualization of the last 3-4 feet of the colon. In principle, it works just like the longer colonoscope. Typically when this scope is used, no anesthesia or sedation is given to the patient. For this reason, it actually may be a more uncomfortable procedure to go through than a complete colonoscopy. The main advantage has to do with the fact that there are many more physicians who have the expertise in this procedure, and the cost is much less.

Virtual Colonoscopy

Recently, a new technique has been developed for colon screening, called virtual colonoscopy. This test is not widely available, and there is no consensus on whether it is a reasonable substitute for performing a colonoscopy. The test requires a bowel prep, just like for colonoscopy. Then a CAT scan is done while at the same time, a dye is inserted into the colon as an enema, using a flexible tube inserted through the anus. A special software package is required to process the images taken, which reconstructs images to give a virtual three-dimensional view of the inside of the colon. This allows polyps to be seen almost as if one is undergoing a colonoscopy.

The test takes about 30 minutes and does not require any sedation. This makes it less inconvenient, since you don’t need to have someone else accompany you, and you could return to all your normal activities almost immediately. The test is less sensitive in seeing smaller polyps, and for this reason, if one relies on this test instead of a colonoscopy, the test should be repeated every five years. If you have a regular colonoscopy, and no polyps are seen, it usually does not need to be repeated for ten years. The other drawback is, if significant polyps are seen, then you will need to undergo another bowel prep and a regular colonoscopy in order to have the polyp removed. Polyps are seen in about 10% of patients who undergo a screening colonoscopy.

It is likely that there will be continued refinements to this screening technique, but at present, it is not considered to be the best screening test for the general population.

Fecal Occult Blood Testing (FOBT)/ Fecal DNA

One of the oldest screening tests for colon cancer is called the “fecal occult blood test”. This basically means that a sample of stool is tested with a chemical which can detect the presence of microscopic amounts of blood in the stool. As discussed on the “Symptoms” page, the presence of blood in the stool, whether visible to the naked eye or in microscopic amounts, can be an early sign of a colon cancer. Before colonoscopy was so readily available, this test was relied on more heavily to decide which patients should undergo more screening. It is still considered part of a routine physical examination, though it has less importance these days.

Fecal DNA

There is another test that can be done using a sample of stool, which has become available more recently. This test involves the identification of DNA material in the stool that gives evidence of cancer cells somewhere in the intestinal tract. The lining cells of the intestinal tract are constantly dividing, and being replaced by newer cells. Older cells are sloughed off and excreted in the stool. If there are any cancer cells somewhere in the colon, these cells also can show up in the stool. There are certain differences in the DNA of the cancer cells compared to the normal colon cells, and these differences can be detected using a very sophisticated analysis of the stool.

The test has some drawbacks. Rather than just a swab of the stool as a specimen, an entire bowel movement must be collected, and it must be sent to a central laboratory. It doesn’t sound like much fun, does it? In addition, the test is not effective for identifying someone who has polyps, which are precursors to colon cancer. It can only find evidence of cancer once a polyp has transformed into cancer. So it really isn’t helping with prevention, only earlier detection of cancer. The test is also moderately expensive, and probably not covered by your insurance company. But perhaps with more refinements, this test may have better utility in the future.

Treatment

Once a colon cancer is diagnosed, the primary treatment is removal. In most cases this requires surgery, but if the cancer is found at a very early stage when it has not grown beyond the polyp where it started it might be removed through a colonoscope. When the polyp is removed, it is examined by a pathologist with a microscope. If the cancer cells are only seen in the tip of the polyp but not at the base where it was cut across then nothing else needs to be done. Your doctor will recommend a repeat colonoscopy to monitor closely for any additional polyps.

If cancer has grown into the base of the polyp or beyond, a segment of the colon needs to be removed. Many people seem surprised at how much colon is to be removed in such cases. The reason for removing an entire segment has to do with how colon cancer grows and spreads. The first place that colon cancer cells might spread is into lymph nodes near the colon. These lymph nodes are found along the blood vessels that supply the colon and these blood vessels and lymph nodes are located in something called the mesentery of the colon. This mesentery is a thick membrane of fatty tissue connecting the colon and small bowel to the back of the abdominal cavity where the blood supply originates. In order to remove enough of the lymph nodes, one has to remove this mesentery, including the blood vessels supplying that part of the colon. The amount of colon removed is determined by which major blood vessels are removed. Since there are about 4 major blood vessels supplying the different colon segments, the amount of colon removed basically is determined by which segment of the colon the cancer is located.

The first segment of colon is on the right side of your abdomen, called the right colon (or ascending colon, which includes something called the cecum), and is supplied by the right colic artery. The next segment of the colon crosses the upper abdomen from right to left and is called the transverse colon, supplied by the middle colic artery. The next part of the colon descends down on the left side of the abdomen, called the left colon (or descending colon), and is supplied by the left colic artery. The next segment forms an S shape called the sigmoid (like the Greek letter for S, or “sigma”), and is supplied by the sigmoid artery. Beyond the sigmoid colon is where the rectum begins.

If the cancer is located in the cecum or ascending colon, a right colectomy is the usual procedure. If the cancer is in the transverse colon, the surgery will remove at least half of the transverse colon, and often the right or some of the left depending on whether the cancer is closer to the right or left side. If the cancer is in the left, or descending colon, the left colon will be removed, and so forth.

In order to remove a portion of the colon, some sort of incision must be made of course. This traditionally has involved making a fairly long opening into the abdomen to allow the surgeon’s hands to get down and around the colon and its blood supply. This method has come to be referred to as the “open” or “traditional” technique, in contrast to a newer method now available. Since the early 1990s, new techniques have been developed which allow the surgeon to use smaller incisions with small instruments rather than hands to do the procedure. These various techniques are referred to as “laparoscopic” or “laparoscopic-assisted” procedures. In many cases, the necessary procedure can be achieved in this way, through a smaller incision. Your surgeon will likely discuss these different options with you and decide which technique seems best for you.

In the past, anytime a portion of the colon was to be surgically removed, the patient had to cleanse their colon, just like what is done for colonoscopy. This involves drinking only clear liquids for 1-3 days, and taking some laxatives or purgatives. We now know that it doesn’t usually make any difference whether the colon is “cleaned out” or not for the surgery, the outcome seems to be the same. And so, in most cases, the surgeons at DeKalb Surgical Associates will not make you go through the “bowel prep” prior to your surgery. There are situations where it still is necessary so you can discuss this further as you prepare for your surgery.

Surgery Expectations

Your office appointment before the surgery will involve a detailed history and physical examination. This helps decide which procedure should be done, whether any additional testing should be done before the surgery and what the potential risks are for you, depending on any chronic medical conditions you have or medications you take. A pre-operative visit to the hospital will be scheduled, where an anesthesiologist will meet with you to discuss what their role will be, and the hospital staff will explain what all will take place on the day of surgery.

You will not need to spend the night before surgery in the hospital, but instead will arrive on the morning of surgery. An IV line will be inserted before being taken to the operating room (OR). Once in the OR, the anesthesiologist will give you some medications which make you fall asleep almost immediately, and the surgery is then performed while you are completely asleep; this is called general anesthesia. When the surgery is completed you gradually wake up and are taken to the recovery room. Once you are awake enough, and over the early side effects of the anesthesia, you will be taken to your hospital room, where your family can join you. Typically you are allowed to have some sips of liquids even on the day of surgery, but don’t expect any food for about 2 days and sometimes longer. In the past, patients always had tubes placed through their nose into the stomach after this type of surgery, but we now know that this usually is not needed. A catheter is sometimes placed into your bladder (called a Foley catheter), and it may be left in place for a day, and sometimes longer.

Your length of stay in the hospital is determined by how quickly your colon function returns back toward normal. Some patients recover faster than others, and so it is a little difficult to predict in advance how long you will need to stay. Some patients actually can go home after only two nights, though this is not the usual case. On the other hand, some patients just don’t feel well enough, or have some problems after surgery, such that their stay goes beyond a week. Your surgeon will visit you daily and keep you apprised of how he thinks you are doing and should give you a running estimate of when he thinks you can be discharged home. Your recovery from the surgery continues after discharge, as you gradually resume a normal diet and level of activity.

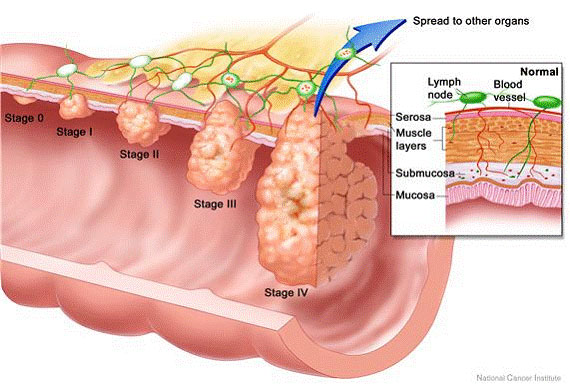

The report from the pathologist regarding cancer usually takes about three days to be reported to your surgeon and then to you. The main details have to do with how large the cancer is, how deep it “invaded” into or through the wall of the colon, and whether any cancer cells are seen in the lymph nodes. The answers to these questions determine what is the “stage” of your cancer, and the stage determines if any other treatment needs to be considered, such as chemotherapy. For patients with smaller tumors and no cancer cells in the lymph nodes, there is usually no recommendation for chemotherapy. On the other hand, for larger tumors, or for cancers that have gotten into the lymph nodes, you will likely need to also receive chemotherapy after the surgery, in order to decrease your risk for having any recurrence of cancer in the future.

Staging

If you already know the stage of your cancer, this section will explain what your doctors are basing that determination on. There is a difference between what’s called “clinical” and “pathologic” stage. If you haven’t yet had definitive surgical treatment (that is, you’ve only had a biopsy), then your doctors will be making treatment recommendations based on the “clinical” stage. For colon cancer, the initial treatment is almost always a surgical removal of cancer, unless there is already evidence of spread to other organs in the body. After the surgery, the stage is revised if needed, based on the additional information provided by the evaluation of the tissue removed.

The method of staging cancers has been well-defined for decades. There is a standard manual that has been agreed upon by virtually the entire international community of cancer experts, which is used as a reference. This manual is updated every few years. The idea is to try to categorize cancers into smaller groups that are likely to behave in similar fashion. This grouping of similar cancers allows doctors to provide more individualized treatment plans. Rather than treating all cancers the same, each stage may be treated in a way that will best fit that subgroup of cancers.

The concept of staging is essential in making the best decisions about treatment. Your surgeon should determine the stage of your cancer at the outset, based on what can be learned about your cancer from physical examination, from biopsy information, and from any imaging studies that might have been done. This is called a clinical stage. Once a definitive operation has been done, the added information from the surgery will then be used to revise the cancer stage if needed. This is called a pathologic stage.

Now, how does the staging system work? For nearly all different cancer types, the stage depends on just three things, summarized by the initials TNM. These stand for: (1) T is for tumor size, (2) N is for lymph node status, and (3) M stands for evidence of metastatic disease, or in other words, cancer spread beyond the lymph nodes. Not surprisingly, this is called the TNM staging system. The group which publishes the guidelines is called the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Most of you will not need any more detailed information on this but the link is there if you are interested in learning more.

For colon cancer, the T part of the stage is determined as shown:

| Tumor size (Invasive Component) | T |

|---|---|

| Non-invasive (cancer “seeds”) | 0 (or “Tis”, for in situ) |

| Extends into the submucosa | 1 |

| Extends into the muscularis (muscle layer) | 2 |

| Extends through the muscularis (muscle layer) | 3 |

| Extends through the serosa | 4a |

| Extends into adjacent organs | 4b |

The N part of the stage is determined as shown:

| Lymph Node Status (in the “Mesentery” of the Colon) | N |

|---|---|

| No lymph nodes with cancer | 0 |

| 1 lymph node with cancer | 1a |

| 2-3 lymph nodes with cancer | 1b |

| Small pockets of cancer cells near lymph nodes | 1c |

| 4–6 lymph nodes with cancer | 2a |

| 7 or more nodes and some other advanced findings | 2b |

The M part of the stage is determined as shown:

| Is Metastatic Disease Present? | M |

|---|---|

| No | 0 |

| Yes, to one “distant” organ or set of lymph nodes | 1a |

| Yes, to more than one place | 1b |

Once each of these factors is determined, the three numbers are combined into a Stage. The higher the numbers, the higher the stage.