If you have already been diagnosed with breast cancer or had a biopsy showing abnormal cells, see Breast Cancer.

DeKalb Surgical provides answers to frequently asked questions related to benign breast problems, including breast lumps and cysts, breast tenderness and pain. Also learn about screening and prevention issues, including mammography, ultrasound, MRI and more.

Breast Lumps and Cysts

I just found a lump in my breast. What should I do?

Any lump in your breast should be checked by a qualified physician to determine what it is. If you are not sure whether it’s really a “lump”, or not, you may wish to wait through a menstrual period to see if the new finding is still present. But if it is a definite lump, you should not delay.

It is not uncommon for me to see a woman in the office who is not sure whether they are feeling a “lump” or not. Sometimes what they describe as a “lump” feels to me like just some thickening of the breast tissue. Distinguishing between a “lump” and thickened breast tissue is not always easy. We rely a lot on any corresponding findings on mammogram or, particularly, on ultrasound, to guide us. If there is a definite finding on mammogram and/or ultrasound, a biopsy is almost always recommended. If the area feels more like a “thickening” to me, and the mammogram and ultrasound don’t show anything, and these situations, a biopsy may not be necessary.

A new lump may simply be a benign cyst, or it may be the first sign of a breast cancer. So it is important to be examined promptly, to see which you might have. There is no need to remain anxious about whether your lump is cancer or not. In most cases, at DeKalb Surgical, if the biopsy is necessary you can usually be done at your very first visit, with a result in just 1-2 business days.

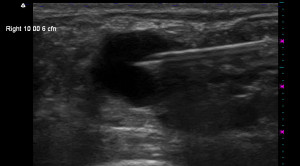

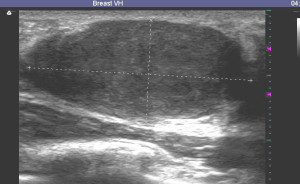

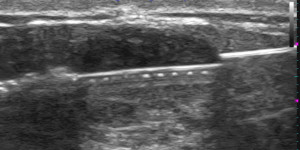

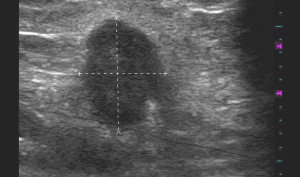

As noted above, ultrasound is frequently used to evaluate a breast lump, and this is often more helpful than the mammogram, though the mammogram of course is important. At DeKalb Surgical, a biopsy is often done at the time of your very first visit for any well-defined breast lump. We utilized the findings on ultrasound to decide if a biopsy is necessary, and then to guide the biopsy. Here are some examples of what different types of breast lumps may look like on ultrasound.

Here is a typical cyst (also showing a needle tip in it):

Here is a typical fibroadenoma, which is a very common finding in teenage girls and young women:

Here is an example of what a cancer might look like on ultrasound:

If a biopsy is done, it is important to be sure that the biopsy is taken from the right place. The ultrasound visualization makes it very clear that the needle is placed within the lump as you can easily see here:

I have a lump, but my mammogram is normal, so it’s not cancer, right?

You must understand that not all cancer shows up on mammography. Any lump needs to be examined by a qualified physician, whether it shows up on mammography or not. If the lump is not seen on mammography, it may be still need to be biopsied. An ultrasound may be helpful. But the most important thing to remember is that if you have a lump, it should be evaluated promptly, regardless of what the mammogram might show.

I had a routine mammogram and it showed “calcifications”, or a “nodule”. I have been referred to a surgeon. Does this mean I have cancer?

Screening mammograms have become an important method to screen for breast cancer. We have learned that mammograms can often detect the earliest signs of breast cancer, at a point in time when it can not yet be felt. Early breast cancer often shows up as a small cluster of calcifications, which look like a small grouping of tiny white flecks on the mammogram, or as a small nodular area which is more white than the surrounding breast tissue. But, these same abnormalities can be caused by breast changes that are not breast cancer as well. Only about one in six of these abnormalities end up being cancer when they are biopsied. But the only way to be sure is to sample the tissue with some sort of biopsy. This means that most of those who have a biopsy will find out that there is no evidence of cancer.

My doctor says I just have a cyst in my breast. What causes cysts? Should I have it removed? Should it be drained with a needle? Will it come back?

Breast cysts are very common. They are frequently quite large, and often a bit tender. They may seem to have popped up overnight, as a very large lump, the size of a grape or larger. Although we don’t know why they occur specifically, it seems they develop as a response to the normal hormone variations that occur through the monthly menstrual cycle. Sometimes they will go away on their own as quickly as they come, but often they remain for some time.

Cysts can be classified as “simple” or “complex”. An ultrasound is especially helpful in evaluating cysts; in fact, if a lump has all the characteristics of a simple cyst on ultrasound, it can be safely “left alone”. But when it can be clearly felt, and doesn’t go away, it may be best to drain it with a needle. This is simple to do, and it can relieve any tenderness. What’s more, there is nothing more reassuring about a new lump in your breast than to make it disappear!

Cysts can come back, but most do not. Some women tend to develop new cysts over and over, and some women develop so many cysts that it seems impossible to try to drain all of them. This situation is challenging, because it makes it hard to decide if there may be a “new” lump hiding in the background of all the cysts. In such cases, it may be best to plan to have your breasts checked by a physician more frequently, perhaps every 3-6 months. Though this is no guarantee of finding any beast cancer early, it should help. Having lots of cysts does not appear to increase your chances of having breast cancer; it just makes it harder to check.

I had a cyst drained, and the fluid looked green. Should the fluid be tested for cancer?

In years past, doctors routinely sent cyst fluid to be analyzed for cancer. But it turns out that the information obtained is not really helpful in deciding what to do, so most doctors have stopped doing this routinely. There may still be situations in which cyst fluid analysis is helpful. This may include cases in which the fluid is crystal clear, bloody, in cases where the cyst looks unusual on ultrasound, or in a patient who has an especially high risk of cancer.

My teenage daughter found a lump in her breast. What should we do?

It is very rare for lumps in teenagers to be cancer, but it should still be checked out by a physician. In most cases, it is a benign growth called a fibroadenoma, which is not cancer, and except for rare cases, will not turn into cancer. If left alone, they usually will eventually go away (regress), but this process may take years.

Fibroadenomas usually have very typical features on ultrasound, and they have a very typical rubbery feel, and can be “pushed around” in the breast tissue very easily, so your physician may be quite certain that your lump is a fibroadenoma even without a biopsy. But, a biopsy is very simple to do, using a “fine needle” or a “core biopsy”, so if you or your doctor have any anxiety about it, a biopsy or excision should definitely be done.

Sometimes it may make more sense to just remove the lump rather than do a biopsy. A lump brings with it a certain amount of anxiety even if a biopsy is “benign”. If you feel that leaving the lump in would cause you too much anxiety, even if benign, then you and your doctor may want to skip the biopsy and just remove it.

Breast Tenderness and Pain

Why are my breasts so tender?

Breast tenderness is a very common symptom. It is rarely associated with breast cancer, but a thorough exam by an experienced physician is important to be sure.

Most women experience at least some increase in sensitivity or tenderness in their breasts as their menstrual cycle In some women this can become quite severe. The tenderness may be diffuse, involving all of the breast tissue, or it may be localized to one breast, or one area of one breast. Though it usually lessens after the menstrual period it may be constant. It is clear that changing hormone levels in the blood stream are the primary explanation, but there may be other contributing factors. Certain medications may increase tenderness, including birth control pills, estrogen or progesterone (Premarin, Provera, Ogen, Climara, Estratest, and others), and medications which contain xanthines (Theodur, caffeine containing stimulants). Caffeine seems to cause increased breast tenderness for many women, though it seems to have no effect in others. Marked breast tenderness frequently occurs in the very early stage of pregnancy also. Sometimes a cyst can develop and enlarge rapidly, causing localized tenderness. Less commonly, an area of infection may occur which can be extremely tender.

If you have recently noticed that your breasts are more tender, you should be sure to do a good self-exam of your breasts. See if can identify a specific area that hurts, and feel for any lumps. Look for any visible changes such as a visible lump, or a dimpling of the skin, or redness. Schedule an appointment with your physician, and take a list of your current medications. Be aware of how much caffeine you are using, including coffee, tea, sodas, chocolate, and any caffeine-containing medications, such as diet pills or stimulants. Be able to pinpoint when your last menstrual period was, and whether is was normal or not. Ask your physician’s office if you should have a mammogram or other studies before your appointment, and if you should bring your mammograms with you.

Will I need a biopsy?

For most women with breast tenderness, the physician’s exam will not identify any problem which needs a biopsy. However, occasionally there is an associated lump, which could be a fluid-filled cyst, an abscess, or a solid growth of tissue. Such findings will likely require a procedure, such as use of a needle, or other sort of biopsy or removal. This may frequently be done at the time of the initial visit. (Please note that some insurance companies do not cover procedures to be done on the same day as your exam. If not, you will be scheduled to return for the procedure after your insurance company has given authorization.)

Cysts can be treated simply with drainage of the fluid through a needle. The pain from the fluid drainage is similar to what you would feel if you have a blood test done. The cyst fluid usually has a greenish, yellowish, or brownish tint. There is usually no need to “test” the fluid if it has this typical appearance.

Abscesses usually require a small incision to drain the infection. For small abscesses, treatment can be done immediately. The infection causes more surrounding tenderness than a cyst, so the drainage procedure is likely to be more painful, but brief. The advantage of immediate treatment may outweigh the extra tenderness. Larger abscesses may require drainage in a hospital setting in order to provide adequate sedation and/r anesthesia.

Solid growths of tissue may be biopsied with a needle at the initial visit. Some anesthetic is injected around the area to be biopsied. The needle is then inserted into the lump to obtain a sample of tissue for analysis. An ultrasound machine is frequently used to place the needle precisely. Most women experience little or no discomfort with the procedure.

What can I do to decrease my breast tenderness?

Once your physician has examined for any possible problems such as a cyst, abscess or possible cancer, there are several things you can do. If you are taking in any caffeine on a daily basis, try cutting out all caffeine products for a period of six weeks. This simple step may be all that is necessary. If your tenderness goes away, you may want to experiment by starting back on caffeine to see if your tenderness comes back. You may find that there is a certain amount of caffeine which you can tolerate without the symptoms.

Both vitamin E and evening primrose oil have been found to be helpful for many women. Though the exact mechanism of action is not known, both supplements have been found to be beneficial in decreasing tenderness. Recommended dosages for vitamin E range from 400 U to 1000 U per day. It is available at all drug stores and many supermarkets without a prescription. As an added benefit, there appears to be a decrease in risk of heart disease in patients taking vitamin E on a regular basis.

Evening primrose oil is carried by many drug stores, though it may be difficult to find than vitamin E. It is more commonly recommended in England than here in the United States. Recommended dosage is up to four tablets per day. It can cause some gastrointestinal side effects, such as bloating or gas, and changes in your bowel movements. These side effects are less likely at lower dosages.

There are many simple measures to try that may help. If your tenderness is predictable with each menstrual cycle, you may want to begin taking on over-the-counter pain medicine, such as Tylenol, Advil, Alleve, or other, for the week before your period. A good hot bath once or twice a day can help. Changing to a different bra is also occasionally beneficial.

Depending on the severity of your tenderness, you may want to use some or all of these measures. Most women will obtain sufficient relief with the steps described above. For the small group of women with persistent disabling tenderness despite all these measures, there is a hormonal treatment which is very effective, but which has a high likelihood of side effects. It involves use of Danazol, a hormone used in treatment of endometriosis. Side effects include changes in menstrual cycle, voice changes, and body hair growth.

Breast Pain

Painful breast tissue is an exceedingly common symptom but is usually of “functional” origin and very rarely a symptom of breast cancer. Many years ago, a surgeon named Haagensen carefully recorded the symptoms of women presenting with breast cancer and found that only 5% of patients had pain at the time of diagnosis. And this was a long time ago when screening mammography was not used routinely; breast cancers were often much larger at diagnosis than they usually are today.

Although not typically a symptom of cancer, breast pain is a common reason for patients to seek medical attention. Breast pain appears to be aggravated by abnormal menstrual cycles and may be seen in young women with menstrual irregularity, as a premenstrual symptom, or when hormones, such as estrogen, are taken during and after the menopause. In addition, fibrocystic change, in its severest forms, may cause disabling breast pain. Although many observers find breast pain and tenderness is aggravated by excessive intake of caffeine, nicotine, or commonly used antihistamines, other investigators disagree.

Fibrocystic Disease

Fibrocystic Change (Cystic Mastopathy, Cystic Mastitis)

“Fibrocystic change,” popularly referred to as “fibrocystic disease,” represents a spectrum of clinical and histologic findings including cysts, nodular breast tissue, and some other changes that have technical terms like “stromal proliferation, and epithelial hyperplasia”. A fibrocystic change appears to represent an exaggerated response of breast stroma (background and supporting tissue) and epithelium (the lining of the breast ducts and lobules) to a variety of circulating and locally (in the breasts) produced hormones and growth factors. Clinically, patients with fibrocystic change have dense, firm breast tissue with lumps and frequently gross cysts or pockets of fluid. This condition is commonly painful and tender to touch. Under the microscope, the lesion recognized as fibrocystic complex contains variously sized cysts, stromal fibrosis (fibrous background tissue), adenosis (overgrowth of glands), and a variable amount of “epithelial metaplasia and hyperplasia”. All these changes can occur alone or in combination and to a variable degree in the normal female breast. Autopsy studies have questioned whether any of these changes, except perhaps macrocysts, are abnormal. In fact, all of these lesions occur commonly in the breasts of elderly patients and appear to have no particular tendency toward evolving into breast cancer. Since these sorts of changes are so common, it really is not appropriate to term it a “disease”. Nevertheless, the term “fibrocystic disease” is so commonly used, it would be hard to get everyone to stop using it. But ideally, the term fibrocystic disease should be abandoned in the absence of any well-defined clinical and pathologic syndrome.

There is no consistent association between fibrocystic changes and breast cancer. It is well established that women who have undergone breast biopsy for any reason, regardless of the underlying pathology, have a slightly higher risk of developing subsequent breast cancer. Moreover, the incidence of finding fibrocystic disease in autopsied breasts from women dying of causes other than breast cancer exceeds the incidence of these same changes in cancer-containing breasts. For those patients with fibrocystic changes, the higher risk appears to concentrate in those whose biopsy specimens show abnormal ductal and lobular hyperplasia and, to a lesser extent, cyst formation. Therefore, the fibrocystic complex appears to be an exaggerated or abnormal response to otherwise physiologic stimuli in most patients and represents a health risk only in certain subsets.

Screening Mammography, Ultrasound, and MRI

I saw in the news recently that the government has said that women under 50 should not get mammograms. What do you think?

There is an agency that evaluates a wide range of preventive and screening services on behalf of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). It is called the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and has been in existence since 1984. Presumably it is an independent panel of private-sector experts in prevention and primary care. Of interest, there are no specialists in mammography or breast surgery on the panel. They comment on a vast array of medical issues, and specifically in this case about when mammograms should be done. They gave recommendations on screening mammography in 2002, at which time they supported it for women in their 40s. They reversed that recommendation in November 2009. This change was based primarily on additional information from results of a study in the United Kingdom, which compared two groups of women between the ages of 39 and 41, and another updated study from Sweden. In these and other studies, there was a decrease in mortality in women undergoing screening, anywhere from 15-31%. The studies also took into consideration the potential down side of screening, in the form of pain from the test, anxiety about results, “false positive” studies (in which there is an abnormality seen on the mammogram that requires a biopsy, but there is no cancer found), and “false negative” studies (there is a cancer present, but it is not seen on the screening mammogram). After taking all this into consideration, they decided the benefits in lowering mortality were not worth the costs of screening in this age group. Updates to the screening mammography recommendations were made in January 2016.

There are some factors that can affect the advantage of screening mammograms. If the films are of poor quality or are read by an inexperienced radiologist, or if any recommended biopsies are done by inexperienced physicians, there may be more harm than good done. So we highly recommend annual, or at the very least biannual (every two years) screening mammograms for women in their 40s, done at a reputable facility such as the Breast Center at DeKalb Medical; if a biopsy is required, be certain the physician is highly skilled in the technique. Our surgeons at DeKalb are members of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, and have extensive experience in biopsy techniques.

I have heard that some digital mammograms are better. Is that true?

There are some advantages to digital mammography, but the pictures obtained with “film screen” are quite good. Some very large comparison studies have shown that digital mammography is slightly better for women with very dense breast tissue, and this typically would be younger women, before menopause. For all others, the image quality is no better, in terms of identifying abnormalities which might be a sign of an early breast cancer.

Just like the digital cameras so prevalent today, digital mammography has advantages in terms of storage and retrieval of images, and in taking good pictures to start with. Most women will note that the time necessary to have the mammograms done is much shorter, and therefore more convenient. The image can be adjusted for contrast, brightness, and magnification, without having to repeat the study. And it can be stored electronically, making it much more accessible for comparison with future films, or for copying for other physicians who may need to review them. So, if your mammogram center is NOT using digital technology, don’t be too concerned. The training and experience of the radiologist are much more important than the type of image used.

DeKalb Medical has been using digital technology for mammograms since about 2008. All our radiologists are trained and experienced in reading mammograms, with each reading thousands of mammograms annually. The equipment is upgraded routinely. If you would like to schedule a mammogram at DeKalb, you can call 404-501-2660.

Three-D mammography, also called digital breast tomosynthesis, is being offered at more and more mammography centers and is currently available at DeKalb Medical Breast Center. As the mammography picture is being obtained, the Xray source rotates slightly around the breast. This is similar to how a CAT scan image is obtained. The result is that the images of the breast can be viewed as if one is looking at thin slices of the breast tissue, one at a time. The result is greater accuracy in deciding whether there is really something in your breast to worry about or not.

Studies evaluating 3D mammography show that in comparison to regular mammography, fewer women will need to be called back for further evaluation (either more imaging, or a biopsy), and at the same time, fewer cancers are missed. It is particularly helpful in women with dense breast tissue. In general breast tissue becomes less dense with age.

Are there any drawbacks to 3D mammography? The dose of radiation required is a bit more than with regular mammography, but this is still considered an acceptable dose. It is more expensive than regular mammography, typically about $100 more, and not all insurance companies cover them. Medicare does cover 3D mammography.

I have a lump, but my mammogram is normal, so it’s not cancer, right?

You must understand that not all cancers show up on mammography. Any lump needs to be examined by a qualified physician, whether it shows up on mammography or not. If the lump is not seen on mammography, it may still need to be biopsied. An ultrasound may be helpful. But the most important thing to remember is that if you have a lump, it should be evaluated promptly, regardless of what the mammogram might show.

I had a routine mammogram and it showed “calcifications”, or a “nodule”. I have been referred to a surgeon. Does this mean I have cancer?

Screening mammograms have become an important method to screen for breast cancer. We have learned that mammograms can often detect the earliest signs of breast cancer, at a point in time when it can not yet be felt. Early breast cancer often shows up as a small cluster of calcifications, which look like a small grouping of tiny white flecks on the mammogram, or as a small nodular area which is more white than the surrounding breast tissue. But, these same abnormalities can be caused by breast changes that are not breast cancer as well. Only about one in six of these abnormalities end up being cancer when they are biopsied. But the only way to be sure is to sample the tissue with some sort of biopsy. This means that most of those who have a biopsy will find out that there is no evidence of cancer.

I went for my routine screening mammogram, and I was told to come back in 6 months for another mammogram. Is it okay to wait that long if there’s an abnormality on the mammogram now?

It’s good that you are having annual mammograms done. Of course, every woman hopes that nothing abnormal will be seen, and in fact, about 90% of women do indeed have a “normal” mammogram. And of the other 10%, even though the mammogram may show something abnormal, most of these women don’t have cancer.

Abnormalities seen on mammograms fall for the most part into 2 categories; suspicious calcifications, or densities. Not all calcifications are suspicious, and it would be too complicated to go into all the subtle distinctions that are considered in evaluating any calcifications. Generally speaking, the calcifications which are small, clustered (and multiple), and variable in shape and size (this is called pleomorphic), are the ones that should be biopsied. Now if the radiologist sees just one or two calcifications, or if they are not that variable in size, or if for some other reason, they aren’t that suspicious, he may recommend a “short-term followup”, which usually means, a repeat mammogram of just the involved breast in 6 months. It doesn’t really make sense to recommend a biopsy when the findings are not that suspicious since it would require doing biopsies in 50 women to find the 1 of 50 who actually has cancer. As it stands, only about 15% of the abnormal calcifications which are biopsied (BIRAD 4 cases) are cancer; the other 85% of suspicious calcifications are due to benign changes in the breast tissue.

It is important that the radiologist reviewing your films has lots of experience reading mammograms. At our institution, all the radiologists who read mammograms are reading thousands of studies every year. Our facility is accredited by the American College of Radiology. We use the most up to date technology for digital mammography, which provides high-resolution images, and with much less inconvenience for the patient (rarely do the pictures need to be “done over”).

Those women who are requested to return for follow-up films in 6 months in most cases will be given further reassurance with the 6-month film and then return to an annual schedule. A few women may be advised to have a biopsy based on the followup. If you feel anxious about being told to come back in 6 months, you should ask your primary care physician for a referral to DeKalb Surgical Associates for a breast consultation. We are experienced in evaluating breast abnormalities and will carefully review your specific case, including the findings on physical exam, and on mammography. If appropriate, ultrasound can be performed at the time of your visit for additional information (though for calcifications, ultrasound rarely is utilized).

I was told that my mammogram was read as a BIRAD 4. What does that mean?

When your mammogram is read by the radiologist, he will categorize the findings according to whether anything looks suspicious or not. The American College of Radiologists set up standards for rating mammograms, which is called BIRADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System).

| Category | Diagnosis | Number of Criteria |

| 0 | Incomplete | Your mammogram or ultrasound didn’t give the radiologist enough information to make a clear diagnosis; follow-up imaging is necessary |

| 1 | Negative | There is nothing to comment on; routine screening recommended |

| 2 | Benign | A definite benign finding; routine screening recommended |

| 3 | Probably Benign | Findings that have a high probability of being benign (>98%); six-month short-interval follow-up |

| 4 | Suspicious Abnormality | Not characteristic of breast cancer, but reasonable probability of being malignant (3 to 94%); biopsy should be considered |

| 5 | Highly Suspicious of Malignancy | Lesion that has a high probability of being malignant (>= 95%); take appropriate action |

| 6 | Known Biopsy-Proven Malignancy | Lesions known to be malignant that is being imaged prior to definitive treatment; assure that treatment is completed |

The BIRAD 4 classification refers to findings for which the radiologist feels biopsy should be considered, even though it might not be cancer. This designation covers a wide range of suspicious findings, and for this reason, some radiologists will further categorize the findings as 4a, 4b, or 4c, indicating progressively higher suspicion. For example, if the radiologist sees a group of three tiny calcifications, not very tightly clustered, and all rounded, they may feel biopsy is appropriate, even though these are most likely benign, and so may designate this as a BIRAD 4a. If they sees a “tight” cluster of numerous tiny calcifications that are variable in shape and size, and perhaps showing branching, they would predict that these are much more likely to indicate cancer, and may designate these as BIRAD 4c. In most cases, both of these situations are going to require a biopsy, even though the level of suspicion is quite different.

I had an abnormal mammogram and have been told to see a radiologist or surgeon to have a biopsy done. What does that involve?

It is important that in addition to annual screening mammograms after age 40, you should have an annual breast exam by a physician who does a thorough physical exam of your breasts. This is especially important if your mammogram is abnormal. If you are referred for a biopsy, and no breast exam is done beforehand, you might not have the proper biopsy method, or there may be findings missed that would alter the recommendations for biopsy. The surgeons at DeKalb Surgical Associates are highly trained and skilled in the assessment of breast problems, particularly mammogram abnormalities. In most cases of BIRAD 4 abnormalities, you would be scheduled for a stereotactic biopsy. But if the abnormality corresponds to something the surgeon can feel, or can see on ultrasound, a core needle biopsy with ultrasound guidance is usually a better option, and this can usually be done on the same day as your first visit.

A stereotactic biopsy is a clever method designed to obtain a small but sufficient amount of tissue from the breast for biopsy when the area of suspicion cannot be felt, but is seen on the mammogram. It requires some sophisticated equipment, and a skilled physician, but usually is relatively easy for the patient. You will lie on your stomach on a special flat table that can be raised up; your breast drops through an opening in the table. A mammogram plate holds your breast stationary while digital images are taken at two slightly different angles. This allows the physician to precisely localize the abnormality in your breast, using a computer that is hooked up to the table. After injecting some local anesthesia in the skin of your breast, a core needle is advanced through the skin to the target, and several cores of tissue are removed. An x-ray of the removed tissue will immediately confirm that the suspicious area has been removed. The procedure usually only takes about 20 minutes, and is usually painless after the local anesthetic injection.

In most cases, the physician will place a small metal marking clip in the area where the biopsy was taken. This clip is about the size of a tooth filling, and will not be felt, will not move around, and will not set off any metal detectors. This marker is important whether you have cancer or not. If the biopsy shows cancer (results will usually be available in 2-3 days), your surgeon will need to remove more tissue from around the biopsy area. Since the original suspicious abnormality may have been completely removed with the biopsy, the marker will be a certain way of knowing precisely where the biopsy was done. If you don’t have cancer, the marker will remain permanently in your breast, documenting that the suspicious area has been adequately biopsied.

I was seen by a surgeon because of an abnormal mammogram, and was scheduled to have surgery. They are going to put a wire in my breast, and then take me to the operating room for the biopsy. Is there a simpler way to do the biopsy?

In most cases, the initial biopsy can be done without placing a wire, and without having to go to the operating room. Since most such abnormalities on a mammogram are benign, it’s usually better to do a less invasive biopsy initially, rather than going to the operating room for a surgical biopsy. There are exceptions to this, but the surgeon should have given a logical explanation for why a less invasive procedure was not chosen. If you don’t feel comfortable with the recommendation for an open surgical (excisional) biopsy, you could always request a second opinion.

It is almost always best to know there is cancer present BEFORE going to the operating room. If it is not yet determined whether there is cancer, a less invasive core needle biopsy (either a stereotactic biopsy or ultrasound-guided biopsy) is almost always preferred.

Why isn’t ultrasonography used for screening for breast cancer?

Although ultrasound is vital for the diagnosis and management of breast cancer, and for the evaluation of breast lumps, its role in breast screening is not clear. Mammography has been demonstrated to identify many early breast cancers before anything might be palpable, that is before the cancer is big enough to feel like a lump. The mammogram films show essentially the entire breast, and any abnormalities seen will be studied further. If the mammogram shows something that looks like a nodule, ultrasound is almost always utilized to focus on that specific area. If calcifications are seen on mammography, ultrasound would rarely be beneficial, such calcifications are not well seen by ultrasound.

Since microcalcifications are one of the main abnormalities that help us find early breast cancer by screening, ultrasound is not helpful, since microcalcifications are rarely seen on ultrasound images. In addition, there is no standardized method for recording ultrasound images of the breast.

The ultrasound is extremely valuable to focus on one particular area in the breast, once an area of concern has been identified either by palpation or by detection of a nodule on mammography. In this case, the ultrasound is excellent at distinguishing between solid and cystic lesions, and also is very good at characterizing solid lesions as likely benign or malignant (cancer).

Is an MRI better than a mammogram for finding breast cancer?

This is one of those questions that has a very complex answer, and the answer may change over the next few years. MRI stands for “Magnetic Resonance Imaging”, and is a very sophisticated method of viewing anatomy in the body. It probably first found a valuable niche in medicine for evaluating the back part of the brain, where CAT scans sometimes were lacking in the desired detail. As time has passed, MRI has been applied to virtually all body parts, and now has many daily uses, particularly in evaluating joints and other musculoskeletal abnormalities, particularly the spine, and the pelvis and back part of the abdomen. The breast has been evaluated with MRI as well, and no doubt will continue to have important applications. But doctors are not yet agreed as to how best to utilize MRI for breast problems.

The benefit of MRI in breast problems is its extremely high sensitivity, which means that it can show a very high level of detail, and some hidden cancers (a very small percentage) will not be seen with any other imaging study. The

This is one of those questions that has a very complex answer, and the answer may change over the next few years. MRI stands for “Magnetic Resonance Imaging”, and is a very sophisticated method of viewing anatomy in the body. It probably first found a valuable niche in medicine for evaluating the back part of the brain, where CAT scans sometimes were lacking in the desired detail. As time has passed, MRI has been applied to virtually all body parts, and now has many daily uses, particularly in evaluating joints and other musculoskeletal abnormalities, particularly the spine, and the pelvis and back part of the abdomen. The breast has been evaluated with MRI as well, and no doubt will continue to have important applications. But doctors are not yet agreed as to how best to utilize MRI for breast problems.

The benefit of MRI in breast problems is its extremely high sensitivity, which means that it can show a very high level of detail, and some hidden cancers (a very small percentage) will not be seen with any other imaging study. The downside of MRI has to do with its relatively low specificity, meaning that not everything it “sees” is bad.

With screening mammograms, less than 10% of women will have abnormalities that require more evaluation, and of all the women who have cancer hiding somewhere in their breast, about 97% of them will be in that small 10% group. So mammography does a very good job of sorting out which women have silent cancers, but it does not find 100% of the cancers. With mammography, out of about every 5-6 women for whom we recommend a biopsy, we find 1 cancer.

With MRI, about 25% of women will have abnormalities that require more evaluation, and in many cases, there will be two, three, or even more abnormalities that might require a biopsy. Of all women with cancer hiding in their breast, about 98% will be in that group of 25%. But you can easily see that the number of women undergoing biopsies is 2½ times that required based on the mammograms. There are a few more cancers found, but it is hard to decide whether it’s worth the cost, inconvenience, and anxiety for all the women who don’t have cancer, who now are undergoing biopsies.

At DeKalb Surgical, MRI is used in selected cases, primarily in a subset of the women who are already diagnosed with breast cancer. In addition, women who have a distinctly higher breast cancer risk, due to strong family history (e.g., either a documented carrier of one of the BRCA genes or two immediate family members with breast cancer, etc.), may be screened with MRI. In cases where the likelihood of developing a cancer is extremely high, the use of MRI, even with its low specificity, makes more sense.

As discussed above, the role of MRI is evolving, so our use of MRI may also change as time goes on, and as more data is published about the specific situations which may benefit from its use.

I had a breast biopsy that showed some pre-cancerous cells. What should be done now?

The term “pre-cancerous cells” might be used for different situations. There are some benign cells that are more heaped up and irregular than normal breast cells, which are considered to be an indication that a woman is at higher risk for developing a cancer. There are 2 such categories, atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Although these findings are not cancerous, the possibility of finding a tiny cancer nearby is high enough to consider a larger surgical excision of surrounding breast tissue, if these cell types are seen on a core needle biopsy. Though estimates vary, the possibility of finding a nearby hidden cancer in this case is probably about 10%.

I had a breast biopsy that showed ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). What should be done now?

Although no one ever wants to be told that they have cancer, the finding of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is one of those situations where we truly have found a cancer at a stage where it can be nipped in the bud. The “in situ” phrase means that we can tell for sure that these cells have the POTENTIAL to do their cancer thing (which means, to invade into surrounding tissue and eventually spread elsewhere), but that they have not yet invaded even the tissue right around the DCIS cells.

When DCIS is seen on a biopsy, you will need to have more tissue removed from your breast (usually the additional tissue removed is about the size of an ice cream scoop). This is almost always done as on open surgical excision in the operating room, either with sedation or general anesthesia, though sometimes under local anesthesia. This surgical excision is the most important treatment, and it is necessary to remove enough tissue so that none of the DCIS is seen along any of the margins of the removed tissue.

This is not always as simple as it might seem, because the DCIS can only be seen under the microscope, and the tissue is not usually examined under the microscope until after preserving the removed tissue in formalin overnight. This method gives more reliable information than trying to examine the tissue immediately (called a frozen section). This means that there are some women in whom the margins will show some more DCIS, and this will require another trip to the operating room to remove more tissue. This return to the operating room is necessary more often than you might think, as often as 50% of the time at some centers. At DeKalb Surgical, this is only necessary about 12% of the time. I wish it would never happen, but sometimes even the non-invasive cancer cells can extend along the breast ducts in various directions. Obtaining clear margins is a matter of experience, compulsion with orientation of the tissue for the pathologist, and to some extent, how much additional breast tissue is removed. Our technique involves the use of a customized surgical device that is not yet available for general use, which helps to minimize the likelihood that you would need a second procedure.

Although surgical excision for clear margins is the most important treatment, radiation therapy AND 5 years of hormonal therapy (with tamoxifen) is fairly standard additional treatment, with the intention of minimizing the possibility that you might ever develop another cancer in your breast. Your surgeon should discuss these issues with you in more detail. Probably the most important thing to remember if you have DCIS is that almost all women are cured of their cancer when it is found at this stage.

Screening Mammogram

Mammography is not a perfect screening test, and an understanding of its benefits and harms is incomplete.

- Some cancers will be missed, and some women will die of breast cancer regardless of whether they are screened.

- Many cancers will be found, but most women diagnosed with breast cancer will be cured regardless of whether the cancer was found by a mammogram.

- Some cancers that are found would have never caused problems. This is called “overdiagnosis.” Often, women are called back for further testing because of an abnormality that is not cancer; this is called a “false-positive” result.

- Studies of the benefits and harms of mammography have limitations and inconsistent results. The numbers reported below are estimates based on what most experts consider the best available evidence, but uncertainty about these estimates remains.

Benefits

- Mammography decreases the number of women who will die from breast cancer. This benefit is greater for women who are at higher risk for breast cancer based on older age or other risk factors such as family history.

- The number of women whose lives are saved because of mammography varies by age. For every 10,000 women who get regular mammograms for the next 10 years, the number whose lives will be saved because of the mammogram by age group is approximate.

- 5 of 10,000 women aged 40 to 49 years

- 10 of 10,000 women aged 50 to 59 years

- 42 of 10,000 women aged 60 to 69 years

- If your breast cancer risk is higher than average, you may benefit more from a mammogram than someone with average risk.

Harms

- About half or more of women who have a mammogram yearly for 10 years will have a false-positive mammogram, and up to 20% of these women will need a biopsy. If you do decide to have a mammogram, you can anticipate that you will have at least 1 false-positive finding for which you are called back for additional images and perhaps a biopsy. Most of these findings are false alarms.

- For some women undergoing regular screening, the mammogram may find invasive cancer or noninvasive condition (ie, ductal carcinoma in situ) that would never have caused problems (“overdiagnosis”). We cannot tell which these are, so they will be treated just like all other cancers. Experts are uncertain of how frequently this happens, but estimates suggest that if a woman undergoing a screening mammogram is diagnosed with cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ, there is about a 19% chance that the cancer is being overdiagnosed, and she will receive unnecessary treatment.

Making a Decision

- Experts recommend that women aged 50 to 74 years undergo a screening mammogram every 2 years.

- Whether you are likely to benefit from starting mammograms earlier or having them more frequently depends on your risks for breast cancer and your values and preferences. Each woman may feel differently about the possibility of having a false-positive result or being diagnosed with and treated for cancer that might not have caused problems. It is important for you to consider what these experiences might mean for you. It is also important to consider how you might feel if you decide not to undergo screening mammography and you are later diagnosed with breast cancer, even if the likelihood that mammography would have made a difference is small.

There is an online tool from the National Cancer Institute which you may use to determine with some precision what your personal risk of developing breast cancer is. It’s called the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool.

Here’s a useful decision aid available through the University of Sydney in Australia. It takes about 30 minutes to go through the steps. In the end, it gives you the option of documenting your own personal decision aid.

Comprehensive Information on Screening Mammography

Here is an abstract from an article published the benefits and risks of a screening mammography.

A Systematic Assessment of Benefits and Risks to Guide Breast Cancer Screening Decisions

Lydia E. Pace, MD, MPH; Nancy L. Keating, MD, MPH

JAMA. 2014;311(13):1327-1335. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.1398.

Importance: Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among US women. Mammography screening may be associated with reduced breast cancer mortality but can also cause harm. Guidelines recommend individualizing screening decisions, particularly for younger women.

Objectives: We reviewed the evidence on the mortality benefit and chief harms of mammography screening and what is known about how to individualize mammography screening decisions, including communicating risks and benefits to patients.

Evidence Acquisition: We searched MEDLINE from 1960-2014 to describe (1) benefits of mammography, (2) harms of mammography, and (3) individualizing screening decisions and promoting informed decision making. We also manually searched reference lists of key articles retrieved, selected reviews, meta-analyses, and practice recommendations. We rated the level of evidence using the American Heart Association guidelines.

Results: Mammography screening is associated with a 19% overall reduction of breast cancer mortality (approximately 15% for women in their 40s and 32% for women in their 60s). For a 40- or 50-year-old woman undergoing 10 years of annual mammograms, the cumulative risk of a false-positive result is about 61%. About 19% of the cancers diagnosed during that 10-year period would not have become clinically apparent without screening (overdiagnosis), although there is uncertainty about this estimate. The net benefit of screening depends greatly on baseline breast cancer risk, which should be incorporated into screening decisions. Decision aids have the potential to help patients integrate information about risks and benefits with their own values and priorities, although they are not yet widely available for use in clinical practice.

Conclusions and Relevance: To maximize the benefit of mammography screening, decisions should be individualized based on patients’ risk profiles and preferences. Risk models and decision aids are useful tools, but more research is needed to optimize these and to further quantify overdiagnosis. Research should also explore other breast cancer screening strategies.

DISCUSSION:

Drs. Nancy Keating and Lydia Pace, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston performed an extensive search of published literature regarding the benefits and risks of screening mammography in older women, and summarized their findings. They sought to differentiate among the various age categories of women undergoing screening mammography, comparing evidence of decreased breast cancer mortality versus some defined risks.

As you might guess, the results vary depending on which studies are included. In my reviewing the information provided, it seems likely that there is a 10-20% decrease in breast cancer mortality over a 10 year period, if one includes all women undergoing screening mammography. But two recently reported Canadian trials looking at 25 year results failed to show any benefit in mortality for screening mammography.

The authors also investigated “harms” from screening mammography, emphasizing a high false positive rate, which leads to additional studies, biopsies, anxiety, and “over diagnosis”. The concept of over diagnosis is somewhat difficult to comprehend or explain. The concept of over diagnosis is strongly implied from randomized trials in which half the patients do not undergo any screening. If a study is randomized, it can be safely assumed that there should be a similar number of breast cancers ultimately diagnosed in each group. But what has occurred in these studies is that there is a higher number of breast cancers diagnosed in the screened group than in the unscreened group. The only logical conclusion is that there are some cancers identified at screening which would never have become clinically apparent. However, if a cancer is diagnosed by screening, there is no way to determine if that particular cancer is a clinically irrelevant or one or not, so all diagnosed cancers are similarly treated.

I do feel that the conclusions offered by the investigators are rational. They note that the benefit for screening is higher if it is applied to a group of women who have a higher risk for developing breast cancer to start with. Also, if there are multiple comorbidities, which shorten the patient’s life expectancy, the benefit for screening mammography will be proportionately reduced. Also, the individual’s level of concern and anxiety about a possible cancer diagnosis ought to be factored into the decision-making.

The main problem I see with the conclusion is that there is just not enough time to provide a one-on-one discussion with all women regarding the benefit: risk ratio for them individually, even though it would be nice if we could. This summary hopefully will provide information in a way that will help you make up your own mind, or allow you to focus on some particular questions for your primary care physician. It is important to know that there is no right or wrong answer about screening mammography. But as a general rule, the higher one’s risk, the greater the benefit from screening. The shorter one’s life expectancy is, the less benefit there is to be gained from screening.

As women age, they obviously are moving closer to end of life. Screening mammography plays little role in the last 5-10 years of a woman’s life. Of course, we rarely know when the last 5-10 years of a woman’s life begins. But to the extent that we can estimate or predict that, we can make some rational decision about when to discontinue screening mammography. There are Internet tools for predicting one’s life expectancy. These tools could be utilized to help decide when to discontinue screening mammography. More generally, one might continue screening mammography until one’s general health begins to fail, or if there is some other major disease threatening your life, or if your ability to easily travel to the mammography facility is impaired.

Here is an example of how one might use personal information to decide when to stop screening mammography. Mrs. Jones is 83 years old and generally healthy. She had a sister who died of breast cancer in her 50s. She herself has never had breast cancer. She has no breast symptoms. She has hypertension which is well controlled. She has been getting screening mammograms since she was 45 years old annually. She uses the Internet site http://www.vivalongevity.com/LifeCalculator.aspx to calculate her life expectancy, and gives her a mean life expectancy of 11 years, which would be age 94. She may subjectively conclude that she is probably in the upper quartile of women her age in terms of health, so may reasonably predict that she might live actually to age 96, or 13 years. With this information, she might choose to continue screening mammography for about 3 more years, then stop.

On the other hand, Mrs. Smith, is 79 years old, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, and previous stroke. She uses a different Internet site http://gosset.wharton.upenn.edu/mortality/perl/CalcForm.html (either one could be used, but don’t be surprised that you get different results with each one. Remember, these are algorithms that are just making an estimate based on certain criteria.). Her calculated life expectancy is only 5 years, due to her multiple medical problems. For her, it probably doesn’t make any sense to continue screening mammography, since the benefit for screening is to find cancers which may impact your life expectancy beyond the 5-10 year range. So even if she has a cancer that might be found only on screening, it probably wouldn’t decrease her lifespan if left undetected.

For younger women, say under age 65-70, life expectancy calculations probably play less role in making the decision about screening, unless one has many major medical problems. So at these younger ages, it probably makes sense to simply follow the usual recommendations of screening mammography every year. In some other countries, the recommendation is every 2 years rather than annually though I suspect that women are much less likely to stick with their schedule if a two-year interval is used. But this would be a reasonable option for some women, if their anxiety about a breast cancer diagnosis is low, and there is no pertinent family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

Here is a link to another program for calculating risk of developing breast cancer. This one is available through the Harvard School of Public Health. You can click through the series of web pages to input your individual data, and it will give you an estimate for your breast cancer risk. It is particularly nice in that it can show how you might decrease your risk based on what are called “modifiable factors”, such as weight reduction, nutrition, cessation of smoking or alcohol intake.

Family History

There is no one in my family who has had breast cancer, so my chances of getting breast cancer are very low aren’t they?

Don’t assume that you won’t get breast cancer just because it doesn’t run in your family! Most breast cancers are not inherited, meaning that any female is at risk. If you have a lump in your breast, or if you have a suspicious finding on your mammogram, it must be evaluated carefully, regardless of whether cancer runs in your family.

My mother had breast cancer. Does that mean I will get breast cancer?

If someone in your immediate family has been diagnosed with breast cancer, then your risk of developing breast cancer is increased by about a factor of 2. If there are more than one with breast cancer in your family, your risk goes up further, especially if the cancers occurred at a young age (younger than 40).

Although most breast cancers are not primarily due to genetic factors (related to family history), there is a group of women who carry a gene that carries with it an extremely high risk for developing both breast and ovarian cancer. These genes are called the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. These gene mutations can be identified by a blood test, but the cost is over $2000 currently. Most women do not need to have this test done. But it is usually recommended for women who have two or more young family members with breast cancer, or if there is also a family history of ovarian cancer. Each patient considered for the test must be counseled about what the test involves, and what ae the implications of the test results. If you want more information, please contact our office. The genetic testing and counseling is available through the Kann Cancer Center at DeKalb Medical Center.